Long after the politics have passed, literary quality – or lack of it – remains.

The following is a comment I put together on an episode of the Origin Story podcast produced by Ian Dunt and Dorian Lynskey. The episode covered Ayn Rand and her legacy – while the guys are very unsympathetic to her political position, I was pretty astonished to find that they thought she was a pretty effective fiction writer! This is my response, which became a bit ridiculously long for an inline comment – somewhat edited for clarity and to incorporate my correction. You can see the original here.

(The podcast series is really excellent, highly recommended to check it out)

There is a slight danger of slipping into conspiracism here in thinking that all critics must have had a political axe to grind. There is a simpler explanation: that there really are serious literary defects which become obvious when you are familiar with the history of the form.

Psychological intelligence and literary sensibility

I really do recommend this podcast episode and I learnt a lot from it. I didn’t realise that Rand spent so much time in Chicago and some of those quotes are fantastic. Ian and Dorian’s psychological take is really perceptive: of Rand not being able to live up to her principles, and the comparisons to [Jordan] Peterson are really just spot on (complete with the physical disintegration we’ve recently seen him go through).

But when they suggest that The Fountainhead is: readable, has good plotting … I hope they never become literary critics! Joking aside, I would take issue with the idea that the universal critical panning of the novels was politically motivated.

Dorian talks about how he wouldn’t like to be a critic defending Leni Riefenstahl’s technical importance in the history of filmmaking. But in my limited knowledge of cinema, critics have been open in their technical appreciation despite the deeply unpleasant ideology: Riefenstahl, as well as films like Birth of a Nation, are discussed as almost obligatory milestones in the the art (grudgingly, perhaps – but always with regard). Especially in the 50s and early 60s, the terrain would surely not have been particularly politically unfavourable to Rand’s position (the anti-Communism, anti-Fascism can hardly have been that unpalatable). Think about the modern literary reputation of someone like Cormac McCarthy – a man with a worldview of fairly niche appeal (deep conservatism, pessimism and fatalism on the human condition) – who is nonetheless critically acclaimed as a strong stylist.

There is a slight danger of slipping into (what they eloquently call) ankle-deep conspiracism here in thinking that all critics must have had a political axe to grind. There is a simpler explanation: that there really are serious literary defects which become obvious when you are familiar with the history of the form.

This doesn’t detract, of course, from Rand’s longstanding popularity. But there’s a good argument to be made for the continuity of the development of the novel as a literary form, explaining a unanimous critical rejection of the quality of a work as just not good enough to meet that form. A work having popular appeal doesn’t exempt it from that kind of criticism – while we might be interested in the psychological reasons something is popular, we don’t need to conjure up literary virtues as the only explanation for something selling well.

This is an elitist position of course – but Rand hardly has any defence there.

The podcasters were spot on with the connection to Socialist Realist novels. There’s a reason nobody reads, say, Chernyshevski or Cement by Gladkov as works of literature – and why they do, for example, read Dostoyevsky, even though it’s full of 19th century Christian mysticism. It’s not because we’re all virulent anti-communists. It’s because, in strictly literary terms: they’s rubbish. (random quote: “Tamed, he gnashed his teeth from the splinter in his brain, he was large boned, dashing, his jaws clenched so his cheeks fell in”). Long after the politics have passed, literary quality – or lack of it – remains.

The problem I think comes from another nice insight the podcasters talked about: the insistence on a simplified view of the world. Where the artform is a strong means to convey style – in film, say – or when the artist is a virtuoso stylist, this bold statement can be sufficient. I think this is why Ian picked out the (perfectly ok, but not amazing – Rand is no great stylist) description of the city street at dusk. In Rand’s novels the need to continuously bash the reader over the head overrides plot, character and style. She is not primarily interested in naturalistic description, so Ian’s passage isn’t really typical (and I note he didn’t choose any of the godawful dialogue!). Here’s the passage in full:

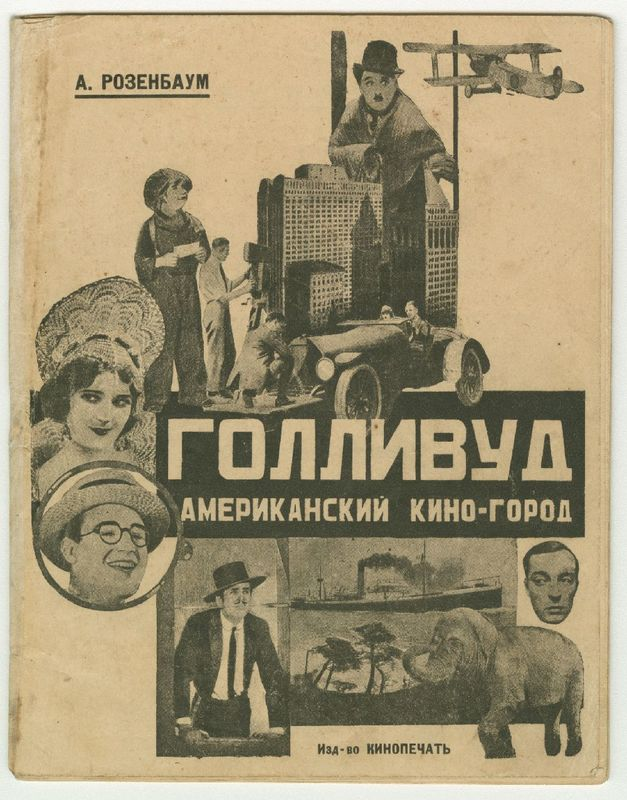

Today strict, business streets of concrete stretch through the suburbs of Los Angeles. Skyscrapers pierce the sky. People, for whom 24 hours is not enough time in a day, stream in a constant wave over its boulevards, smooth as marble. It is difficult for them to talk with one another, because the noise of automobiles drowns out their voices. Shining, elegant Fords and Rolls-Royces fly, flickering, as the frames of one continuous movie reel. And the sun strikes the blazing windows of enormous, snow-white studios.

Every night an electric glow rises over the city.

The origin of this passage is actually really unusual and rather illuminating. It isn’t in fact from the novels, but was written as part of a pamphlet “Hollywood: American City of Movies” (Gollivud: Amerikanskii kino-gorod) under her original name of Alyssa Rosenbaum the year before she emigrated (1926). So this passage was written in Russian and the translation is not hers. It’s perhaps telling that the strongest writing is not part of the fiction and was not in English.

Roark and co must be one-dimensional (and impossible for Rand to live up to) and this destroys all psychological tenability of all her characters. To make up for this an author needs to have a lot else going on, and there is a good reason why this isn’t the case here.

Romantic Road

Rand is an anachronism in a time after modernism had already peaked.

Rand is writing in a Romantic mode: Victor Hugo as the episode mentions is the key influence. But this essentially emotional vision is hamstrung by the need to exterminate whim and make everything rational – a hybrid mess that makes no sense. So we have diatribes against emotion set in emotive language (which is hard to take seriously – presumably this is what our podcasters meant when they said she is funny! Surely, but not intentionally) … coupled with romantic heroes that are cardboard cutouts, and so are totally unsatisfying on a gut level. Roark is a total non-entity, almost a stuffed dummy that seems to get moved from scene to scene – and as you observe Galt is kept out of the way for most of Atlas Shrugged.

Finally, why is Rand writing like Victor Hugo in the 1950s? This is 30 years after Ulysses, the same years Nabokov was publishing Lolita. Whenever I read Rand I always wonder why she is writing a Victorian novel in the 1920s. Then I remember I’m being mislead by the art-deco pop culture and it was actually written 30 years after that. She is an anachronism in a time after modernism had already peaked.

Naturally, the objection is that the appreciation of Rand’s work is not logical or literary but an emotional response – and I think that’s at root true. But here’s the thing – you can go and read Hugo or Hardy for something much better, delivering the same punch without constantly being hypocritically scolded for “emotionalism”. If you want scalpel-sharp, cut glass, logical prose that does something formally new: have I got some Muriel Spark for you (The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie was published in 1961!).

Similarly, if you really want the sui-generis, individualist philosophy of the elite, Nietzsche will make a much more interesting case (80 years earlier) without the obvious errors. This falling between stools – because she will not read and has no understanding of the history of the form or the competition – is one reason she’s a lousy novelist as well as philosopher. The podcasters correctly identify this in her philosophy but I think are being too generous to her novels (where the bar, really, should be much higher – how many thousands of novels are forgotten while this continues to be read?).

Jon bangs on about Nabokov

I often like to compare Rand to Nabokov, another “white”(ish) Russian emigré who fled the revolution and ended up in America. Indeed, Rand knew Nabokov’s sister and even attended the same school.

Nabokov was also a strong anti-communist and anti-fascist – he had reason enough, after his father was assassinated and his brother killed in a concentration camp. But his works are full of humanism that really has preserved them – pick up any of those American novels, and apart from the (spot on) period details they could have been written yesterday. He’s funny, really funny (often about terrible things). And every year I re-read them, and they become richer. The Defense and Pnin mean something totally different to me now, 20 years after I first read them. I just don’t think Rand’s work has that kind of depth.

I can totally understand going through a Rand phase (as a teenage boy, of course). But really, this is literature to grow out of.